The establishment of WGH (150 years ago) and Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg (50 years ago) are significant milestones that have shaped healthcare in Manitoba. These hospitals influenced healthcare advances throughout Canada and the world.

- Founding of Winnipeg General Hospital

- The founding of Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg

- The founding of the Manitoba Rehabilitation Hospital – D.A. Stewart Centre (Respiratory Hospital)

- Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg

- Flood of 1950

- Transplant Manitoba Milestones

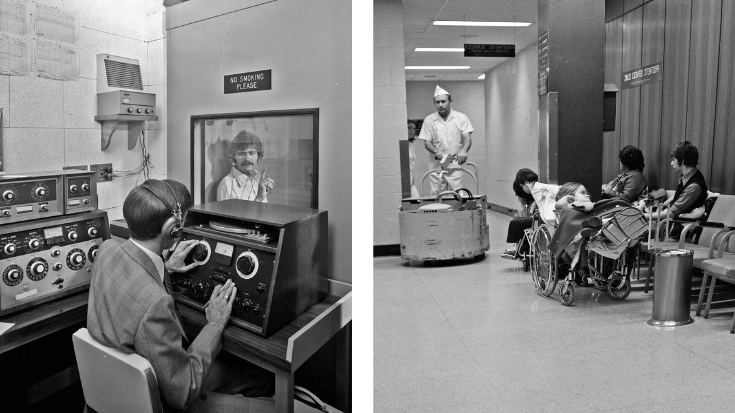

- No Smoking Policy 1973

Winnipeg General Hospital – Manitoba’s First Public Hospital

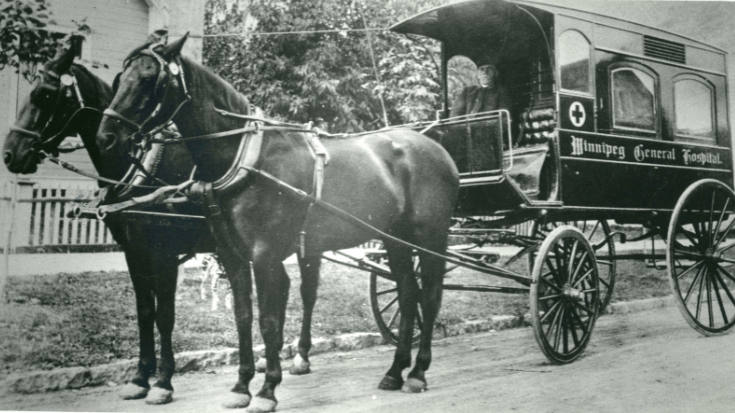

It was the early 1870s and Winnipeg was a town of 1,500 people and roads that were often impassible muck. The primary water source at the time was the Red River – an unhealthy supply which carried sewage from homes, livery stables, and farms. When an epidemic of typhoid fever struck in 1871, the community did not have a public hospital to contend with the illness or deal with even routine medical problems.

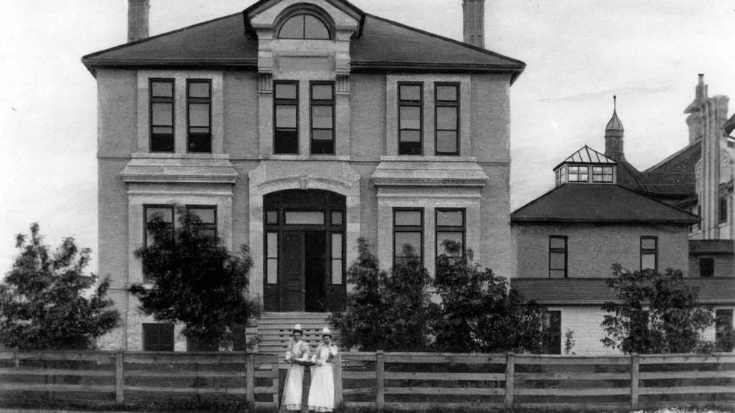

A group of prominent Winnipeg residents recognized the urgent need for a public hospital to serve the city and the new province of Manitoba. They met December 13, 1872 and wasted no time creating the Winnipeg General Hospital (WGH). Five beds were set up in a room above a pharmacy at the corner of Main Street and Notre Dame East.

Winnipeg General Hospital’s first patients

- The first patient was admitted on December 24, 1872 suffering from typhoid fever.

- Two more patients were admitted on January 1, 1873 with gunshot wounds.

Establishing the hospital campus

By Spring of 1873, the hospital had moved to a second location and was encountering financial difficulties. Federal funds were not available, and the hospital directors had to reach into their own pockets to keep the hospital afloat. A dedicated building was needed to care for the health issues and concerns of Winnipeggers and the community rallied.

Churches took special collections, the provincial government consented to a modest grant, and the “Ladies of the Province” organized fund-raising events which raised $1,345.80 of the $1,818.00 needed for construction of a new, dedicated building. Plans for the new hospital were drawn up free of charge by notable architect and civil engineer Walter Moberly, and a breakthrough in the campaign came when A.G.B. Bannatyne donated property on Nena Street (now Sherbrook Street).

Thanks to the generosity of these benefactors, WGH occupied a brand new two-storey building (the first structure it actually owned) in October 1875, and the Nena Street location became the permanent home for the hospital.

Caring for a growing population

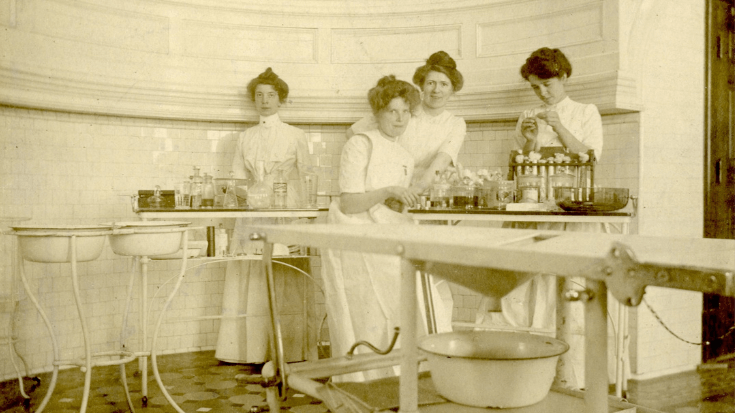

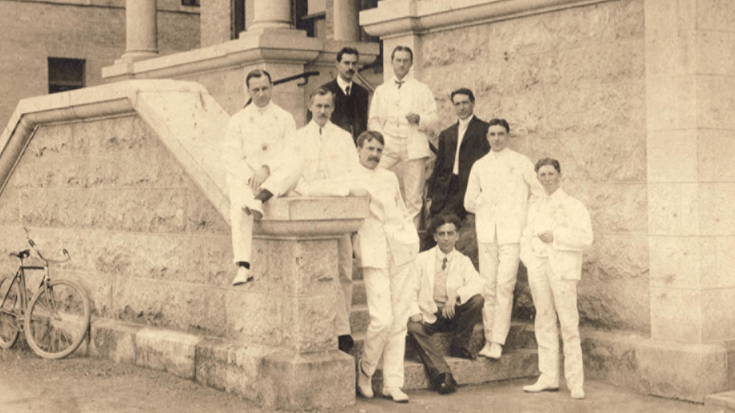

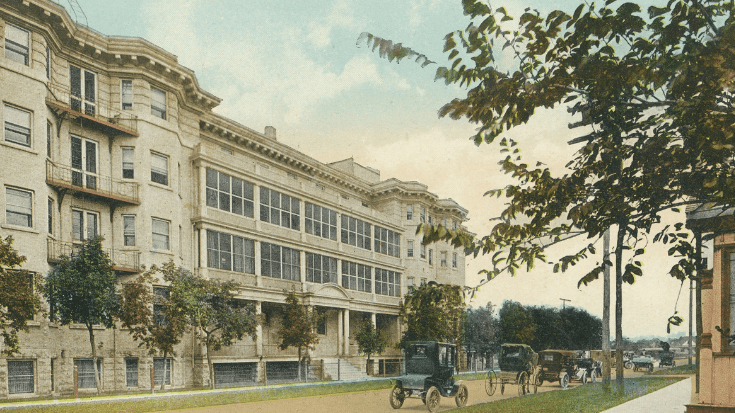

Soon after, Canadian railways reached Winnipeg and the population boomed with some 40,000 new arrivals to Manitoba between 1876 to 1880. By 1921 the city’s population had reached 179,000. As the number of residents grew, so did the need for more staff, health services and a larger campus. New buildings were added, and older structures were replaced by more modern facilities. Training institutions were founded (the Manitoba Medical College was in 1883 and WGH School of Nursing in 1887 – each the first of their kind in Western Canada) and by the 1950s, WGH had developed additional apprenticeship and teaching programs and boasted more technical training programs than any other hospital in Canada.

This year marks 150 years of leadership, compassion and innovation at WGH (now Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg). WGH was founded by community leaders whose vision was to improve the health and well-being of their community by making critically important health services available to everyone. This foundation of leadership, commitment to services and proactive pursuit of innovation and improvement continues to live and grow in what we now know as HSC Winnipeg.

A history of firsts:

From the beginning, dedicated staff at WGH prioritized the patients’ needs and were determined to provide a range of services to patients and their families.

- The first Social Work Department in a Canadian hospital in 1910.

- The first (and only) hospital with a dental clinic in Western Canada in 1912

- The first tuberculosis mobile testing units dispatched in 1925 to remote areas of the province, particularly in Indigenous communities where the disease was prevalent

- The first fetal transfusion in North America

- The first and most modern Intensive Care Unit in the world opened in 1966.

- The first kidney transplant in Manitoba in 1969

A Hospital for Children:

The founding of Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg

A determined nurse with a passion for adventure was the driving force between the creation of a specialized hospital for children that would eventually become part of Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg. Annie Bond, was the driving force behind the creation of The Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg, which opened in 1909.

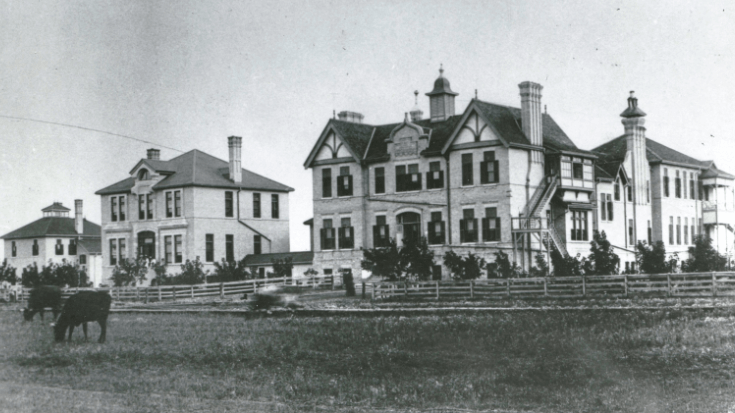

Soon after arriving in Winnipeg in 1903, Annie Bond convinced the local branch of the National Council of Women that Winnipeg needed a facility specializing in care for the community’s children. A compelling presenter, Annie’s vision soon resulted in the formation of volunteer guilds and funds being raised. In 1909, a house that had once been the home of Lieutenant Governor Sir John Christian Schultz was rented for $40 per month.

The house, located on Beaconsfield Street in the Point Douglas area, was rundown but quickly repurposed to open as a hospital on February 6, 1909. It had a capacity of 15 patients, an additional 15 more could be cared for during summer months in the screened in veranda and an outpatient department in a former woodshed. At opening, a staff of one nurse, a maid-of-all-work, and an on-call contingent of physicians and surgeons were in place to care for one sick baby. The hospital was quickly filled to capacity and had a waiting list.

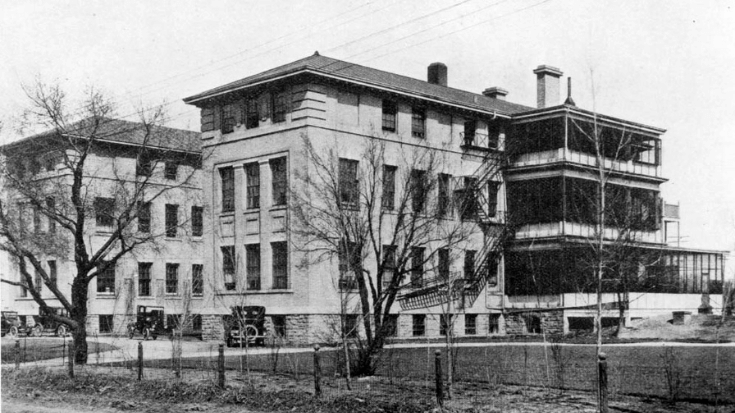

A new fundraising campaign began, led by a group of local business owners, with the goal of building a new and much larger hospital. On November 27, 1911, a new three-story Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg was opened on three and half acres of land located on Aberdeen Avenue along the banks of the Red River. Now the site of the Holy Family Nursing Home, the hospital opened with an increased capacity of 100 patients.

By 1920, admissions at the new Children’s Hospital reached 2,000 patients annually. Over time the facility expanded to provide other services, adding an outpatient wing, a diabetic clinic, and a squint clinic (which included special equipment for eye music exercise). By 1945 discussions were underway to move Children’s Hospital to the same area as the Winnipeg General Hospital (WGH), as part of work to establish a centrally located “Manitoba Medical Centre” campus.

With fundraising underway for the next location of the Children’s Hospital, Winnipeg experienced the massive flood of 1950. The riverbank setting of the existing hospital became problematic, with water filling the basement and threatening the hospital’s electrical and mechanical systems. Children were discharged or moved with staff to receive care at Deer Lodge Hospital, a facility caring for war veterans.

On December 11, 1956, the new $4-million Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg opened at the WGH campus on Bannatyne Avenue, enabling Children’s to draw upon the resources of its neighbouring institutions. In early 1970s, Children’s Hospital became a founding partner in the creation of Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg.

From its humble beginnings in a rented house to today’s substantial facility, HSC Winnipeg Children’s Hospital has evolved over more than 100 years, cementing its status as one of the most important health care facilities in western Canada. Today, HSC Children’s Hospital provides highly specialized and acute pediatric care to patients from every part of Manitoba, Northwestern Ontario and Nunavut in the areas of ambulatory, cardiac, emergency, dialysis, intensive, medicine, mental health, neonatal, and surgery.

Jordan’s Principle: Improving access to care for all First Nation children and their families

Jordan’s Principle is named in memory of Jordan River Anderson, a young boy from Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba. Jordan was born in 1999 with multiple disabilities and stayed in the hospital from birth. When he was two years old, doctors confirmed that his care could continue outside of the hospital, in a special home suited to his medical needs. However, the federal and provincial governments could not agree on who should pay for his home-based care. As a result, Jordan never got to spend even one night at home, and he passed away at the age of five in the hospital.

In 2007, the Canadian House of Commons passed Jordan’s Principle in memory of Jordan. It was a commitment that Indigenous children would get the products, services and supports they need, when they need them. In 2015, it was included in the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission as third of 94 calls to action.

In July 2022, Southern Chiefs Organization hired a Jordan’s Principle Coordinator – with support from WRHA Indigenous Health and HSC Winnipeg – to support First Nation children and their families, throughout their care at the facility. The Jordan’s Principle Coordinator assists First Nation children, youth under 18 and their families in accessing cultural wraparound supports, programs and services to improve health, education, and social outcomes.

Acknowledgement

Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg (HSC) and Shared Health acknowledge that the history of the Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg and of HSC, while populated by significant advancements and innovations in health care, has also included periods and events characterized by discrimination and harm. Over time, efforts have been made to improve care for all Manitobans, learnings and recommendations have been pursued following inquiries and tragic events, and initiatives have begun to engage community and incorporate culturally appropriate and culturally safe care into available health services.

There is more work to be done to ensure that this progress continues and that health services are provided equitably, without discrimination or racism. HSC – and Shared Health – are committed to this ongoing progress.

A History of Pediatric Care in Manitoba

• In the early days, pediatricians frequently wore bow ties rather than long neckties. Bow ties can’t be pulled or chewed, and it’s easier to launder a shirt than a tie.

• In 1911, 260 children were admitted to Children’s Hospital, compared to 9,503 admissions to HSC Child Health and NICU and 40,325 visits to HSC Children’s Emergency in 2022/23.

• In 1911, one of the large wards on Aberdeen Avenue was named the Titanic Ward, furnished by the Winnipeg Real Estate Exchange in memory of three of their executives who perished in the Titanic while trying to save the lives of women and children.

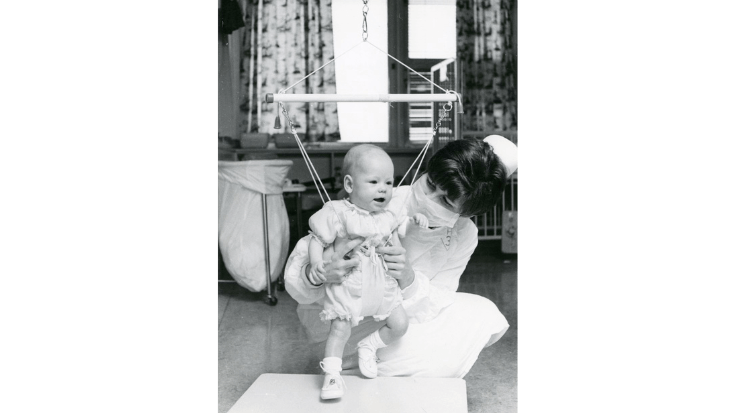

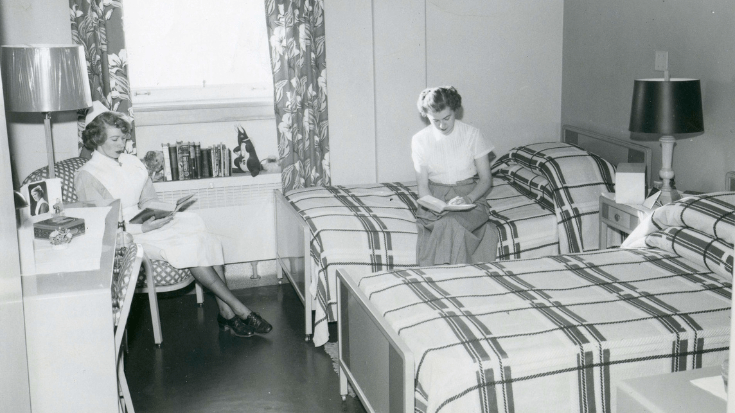

• Years ago, parents were not allowed to stay overnight with their child, and even had very limited visiting hours. Children were generally not told why they were in hospital and were not psychologically prepared for procedures. Today, pediatric units are built to accommodate family members, and allow for patients to embark in play when possible.

• In the Allergy Clinic at HSC Children’s, Drs. Estelle Simons and Zhikang Peng were the first physician scientists to recognize and document a new disease they called Skeeter Syndrome. It consists of large, itchy, red swellings at the sites of mosquito bites, sometimes accompanied by low-grade fever. They were also the first to document that, although rare, mosquito bites can cause anaphylaxis, a sudden, severe and potentially fatal systemic allergic reaction.

• In 1943, founder Annie A. Bond was admitted to and passed away at Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg, the only adult patient ever to be admitted to Children’s.

• A total of 817 nurses graduated from the Children’s Hospital School of Nursing which opened in 1910; the last class graduated in 1969.

• In 1970, Children’s Hospital was one of the first hospitals in the world to begin treating premature infants with lung disease with airway pressure designed to distend the lung. This immediately changed the survival rate of premature infants from 20% to about 80%.

• In 1975, the Department of Services for Native Children was established to ease some of trauma of pediatric patients being in hospital far from home with language and cultural barriers; 50% of pediatric patients at the time were Indigenous.

• Established in 1981, Children’s Hospital Television (CHTV)- a closed-circuit TV station for, with and about children- was the first of its kind in Canada and only the second in North America. Every year, more than 400 patients participate in the 240+ live Good Day Shows produced by CHTV.

• In 1984, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth dedicated the “new” Children’s Hospital building on Sherbrook Street.

• In 2009, Children’s Hospital celebrated a century of service to Manitoba children and their families.

• In 2019, the new HSC Winnipeg Women’s Hospital opened, including a modernized Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

• In 2021, HSC Winnipeg Children’s Hospital Emergency Department established a new Patient Advisory Council, inviting Indigenous parents and youth to provide feedback and cultural perspective in improving care.

• In 2022, the Travis Price Children’s Heart Centre opened at HSC with new cardiac technology and more specialized cardiac care that allows pediatric patients to access care closer to home.

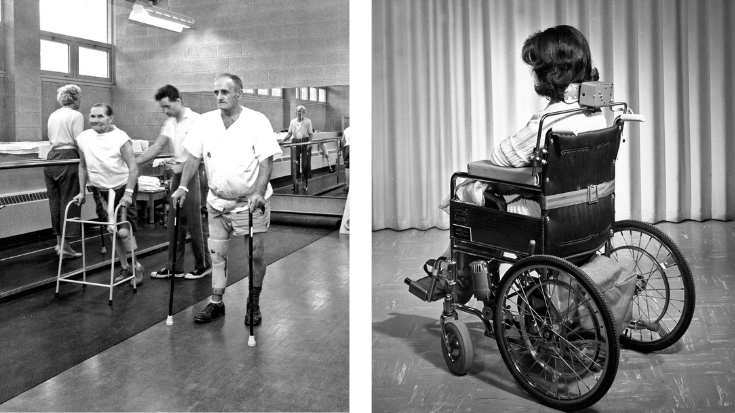

The founding of the Manitoba Rehabilitation Hospital – D.A. Stewart Centre (Respiratory Hospital)

The intersection of Sherbrook Street and Bannatyne Avenue has been home to different health care clinics throughout the history of Winnipeg General Hospital (WGH) and Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg, including the Central Tuberculosis Clinic in the first half of the 1900s, and the Manitoba Rehabilitation Hospital. Today, it’s a part of HSC Winnipeg, as Magenta Fox Zone and Pink Goose Zone, a location where patients receive therapies and treatment to support their recovery and rehabilitation following a traumatic injury, elective surgery, or the progression of a chronic condition.

The Central Tuberculosis Clinic (CTC)

In the early 1900s, tuberculosis (TB) – a highly contagious respiratory disease – was spreading in households and communities at an alarming rate. With high rates of infection worldwide, TB quickly became a significant cause of death in Manitoba.

The Sanatorium Board of Manitoba (now Manitoba Lung Association) was created and tasked with overseeing the startup of institutions that would diagnose and treat individuals with the disease. The CTC was one of the seven sanatoria and Indian Hospitals that were established, opening its doors to patients at the corner of Sherbrook and Bannatyne in 1930.

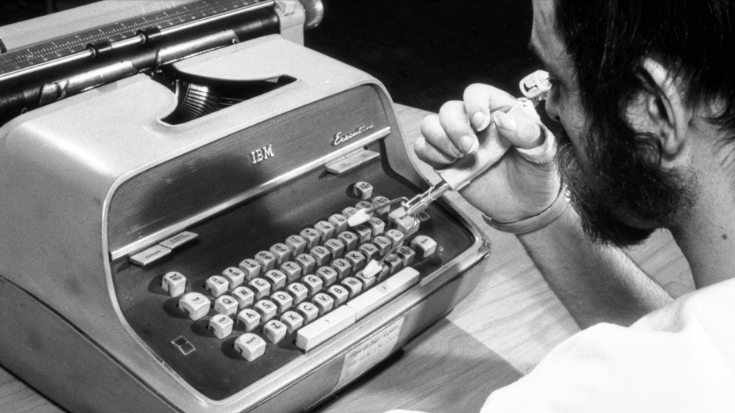

By the late 1950s, fewer cases of TB were being seen as treatment and management of the disease evolved and advancements in medicine and preventative measures were adopted. With TB on the decline, the Sanatorium Board expanded its scope to include rehabilitation services for patients with long-term respiratory illnesses and those living in long-term care settings. Over time, services at CTC expanded to include those for chronically ill or physically challenged Manitobans.

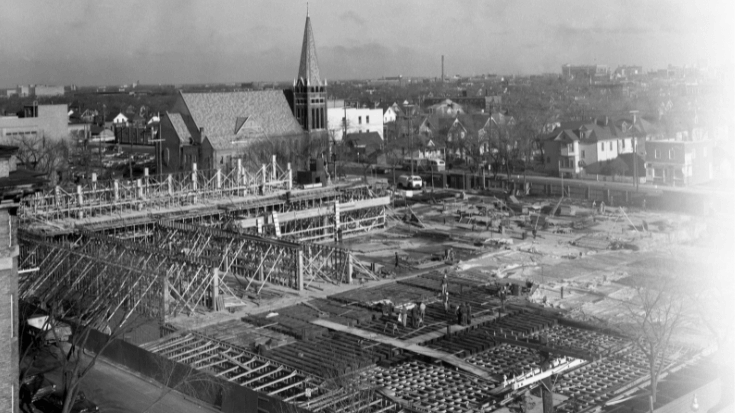

A new era for Rehabilitation

In 1960, a partnership with the Government of Manitoba allowed the Sanatorium Board to advance their focus on rehabilitation services. CTC was demolished (they moved into WGH for two years) and a brand-new building for MRH & TB was constructed at a combined cost of $4.5 million. The construction project would create a new rehabilitation facility while maintaining the TB work which CTC had been doing. In 1962, Manitoba’s first Rehabilitation Hospital opened, a facility renamed in 1968 to honour Dr. David Alexander Stewart for his work in the battle against TB.

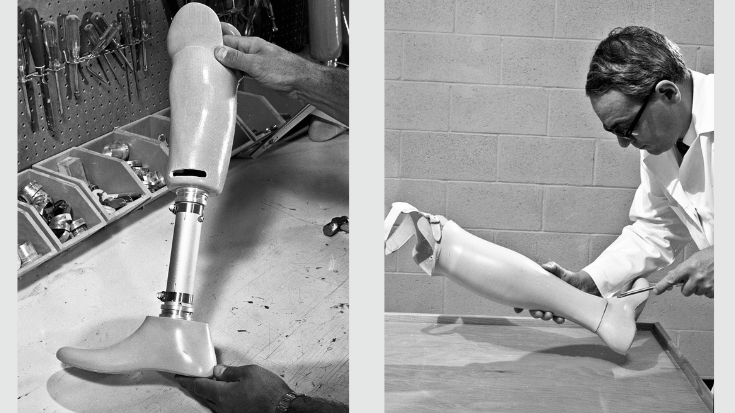

In 1963 the Prosthetic and Orthotic Research and Development Unit (PORDU) was established to develop and research new methods to provide prosthetic appliances and techniques. Initially set up to provide prosthetic appliances and techniques to victims of the thalidomide tragedy (one of three hospitals in Canada to do this), it soon became the place providing prosthetic devices and mechanical aids for all persons with all types of (physical) disabilities. By the mid-1960s PORDU was gaining an international reputation for their work.

The Manitoba Rehabilitation Hospital – D. A. Stewart Centre merged with Winnipeg General Hospital and Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg to create Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg (HSC) in 1973.

Originally, the D.A. Stewart Centre featured a blue and white-tiled mosaic exterior intentionally designed to set a calming and uplifting space for patients. A cafeteria and gathering space inside featured large windows and lots of natural light and a well-kept courtyard allowed patients to venture outside. Today much of its character still remains, but the building continues to evolve with new paint, replaced siding and a walkway joining it to the rest of the HSC Winnipeg campus where patients now use the 24-hour hour food court.

The growth of rehabilitation medicine has involved many advancements and developments that support patient-centered recovery mentally and physically. The care environment is centred around the patient journey through a dynamic, collaborative approach to patient care. Inter-professional teams work together to create and coordinate inclusive and varied treatment programs ranging from occupational therapy, physiotherapy, speech therapy, and hydrotherapy, to various exercise options, activities of daily living and the manufacturing of assistive technology devices and prosthetics in the rehabilitation engineering department which help patients achieve independence.

HSC also provides outreach physiotherapy services to patients in communities as far north as Churchill, helping individuals regain strength, balance and flexibility; and achieve as much functional gain as possible following a traumatic injury, elective surgery, or progression of a chronic condition.

D.A. Stewart Building – a timeline

1930 – An old bakery on the corner of Sherbrook Street and Bannatyne Ave is converted into the Central Tuberculosis Clinic (CTC) to diagnose and treat tuberculosis patients

1950 – The CTC services are expanded to include rehabilitation care for patients with long-term respiratory illness and those in long-term care settings

1962 – The Tuberculosis and Manitoba’s first Rehabilitation Hospital opens in place of the CTC

1968 – The Tuberculosis Clinic of Winnipeg is renamed the D.A. Stewart Centre in honour of David Alexander Stewart, both because of his work in the battle against TB but also to reflect the hospital’s new role in treating all respiratory diseases.

1973 – The Manitoba Rehabilitation Hospital – D.A. Stewart Centre amalgamate with Winnipeg General Hospital and Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg to create HSC Winnipeg, uniting the facilities under a single administration.

Related Links

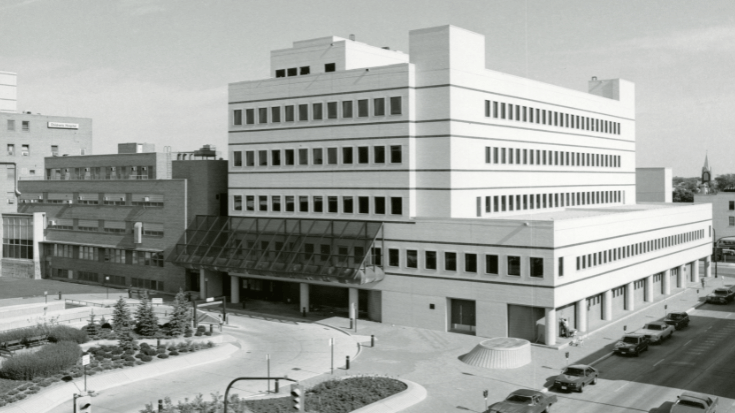

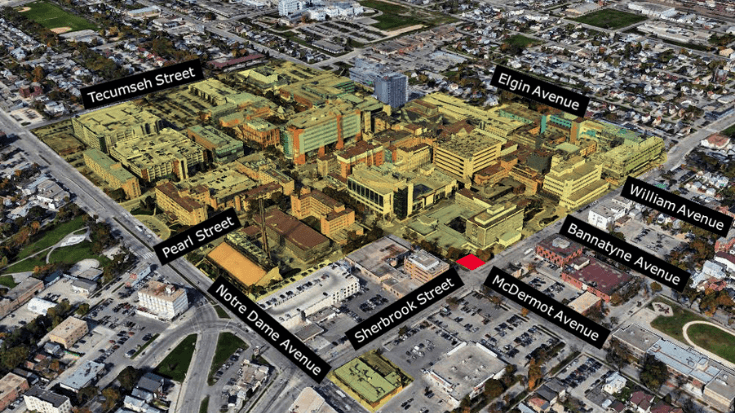

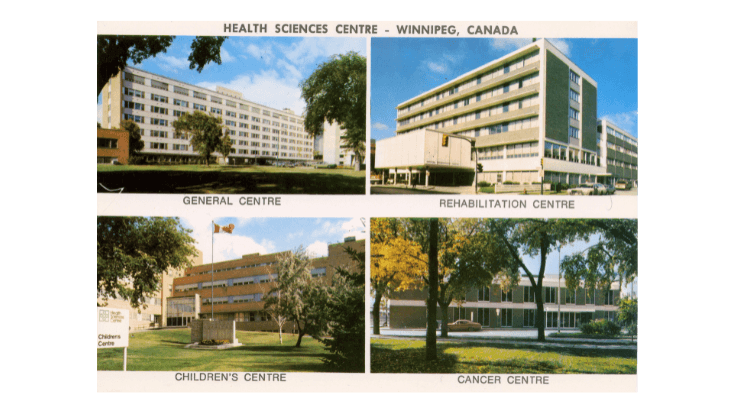

Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg – Created February 1, 1973

24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and 365 days a year, residents of Manitoba, Nunavut and Northwestern Ontario access the specialized skills of health care teams at Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg (HSC Winnipeg). With services ranging from the province’s largest and busiest emergency departments to the delivery of more than half the babies born in Manitoba, HSC Winnipeg supports care and treatment for the most critically ill and injured adults and children. The hospital is also a teaching location, formally affiliated with the University of Manitoba and other post-secondary institutions and welcomes students at various stages of their learning.

Created in 1973, HSC Winnipeg was the result of a merger of several of Western Canada’s most respected health care institutions The Winnipeg General Hospital, The Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg, and The Manitoba Rehabilitation Hospital – D.A. Stewart Centre (Respiratory Hospital). While these separate hospitals had a history of cooperation, they competed for financial resources and the creation of a united facility had long been a subject of public debate.

As early as 1942 the concept of a centralized “Manitoba Medical Centre” near the Manitoba Medical College in Winnipeg was considered an attractive prospect that would create a single administration for global planning and shared electrical, heating and centralized laundry services. In 1956, as part of these centralization plans, the Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg moved to the site, allowing patients to access a wide range of medical services in a central location rather than scattered across the city.

Discussions continued for three decades until the passage of the Health Sciences Centre Act by the Manitoba Legislature on July 20, 1972, and the creation of HSC Winnipeg on February 1, the following year. An agreement with the Manitoba Cancer Treatment and Research Foundation (now CancerCare Manitoba) followed.

Since then, HSC Winnipeg has become a major centre for referrals, teaching and research. It is the designated trauma facility for Manitoba and the only location in the province for transplants, neurosurgery, burn care and most hospital-based pediatric care. The facility provides a range of diagnostic, inpatient and outpatient services to meet the physical, psychosocial, emotional, mental and spiritual health needs of patients of all ages.

HSC has worked to attract a diverse and varied workforce of highly skilled staff and physicians across every specialty that is increasingly reflective of Manitoba’s rich and diverse population.

Over time, the importance of rooting patient care in a culture of inclusion and compassion has been increasingly recognized – and called out in response to events where access to health resources or care have been inequitable with devastating consequences. Recognition of the real and lasting health gaps that exist for Indigenous, Black, and Racialized populations has also grown over time, with efforts underway at HSC Winnipeg and elsewhere in the health system to improve equity and health outcomes for underserved populations.

The inquest into the death of Brian Lloyd Sinclair

In 2008, an Indigenous patient in HSC’s Adult Emergency Department passed away in the waiting room. The death of Brian Sinclair led to an inquest to determine the facts surrounding his death and resulted in changes to program, policies, and practices in an effort to prevent similar events2. Physical changes were made in triage and the Adult ED to improve patient tracking and visibility, with the department completely reconfigured and new roles and processes introduced for improved patient safety2. Today, efforts to address the inequitable experiences and outcomes of Indigenous, Black and Racialized patients continue, with a broad health system commitment to taking the critical steps to disrupt racism and discrimination in all forms. (Link to statement Leadership – Shared Health (sharedhealthmb.ca))

Acknowledgement

Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg (HSC) and Shared Health acknowledge that the history of the Winnipeg General Hospital (WGH) and of HSC, while populated by significant advancements and innovations in health care, has also included periods and events characterized by discrimination and harm. Over time, efforts have been made to improve care for all Manitobans, learnings and recommendations have been pursued following inquiries and tragic events, and initiatives have begun to engage community and incorporate culturally appropriate and culturally safe care into available health services. There is more work to be done to ensure that this progress continues and that health services are provided equitably, without discrimination or racism. HSC – and Shared Health – are committed to this vital work.

With a focus on patient-centred care and close connections to the communities it serves, HSC Winnipeg continues the work of its founders who recognized the value of working together to provide effective and accessible patient care. Working as “one HSC” across programs and services, in close partnership with other health organizations, facilities and communities, HSC Winnipeg continues to grow and respond to changing needs, while providing quality, compassionate care for those who come through its doors.

Significant HSC Capital Projects Over the Years

A number of capital projects over the years have shaped the current HSC Winnipeg campus since 1973. Expansions and construction projects include the Thorlakson Building, PsycHealth Centre, Kleysen Institute for Advanced Medicine, Diagnostic Centre of Excellence, and new Women’s Hospital.

Ann Thomas Building

The current 286,000 square foot glass and Tyndall stone Ann Thomas Building took four years to build, before it opened to patients on January 11, 2007. Housing adult and pediatric emergency departments, an ambulance garage, as well as pediatric, surgical, and medical intensive care units, coronary care units and central sterilization and processing facilities1 the building was built to meet the needs of an increasing volume of patients.

Women’s Hospital

The new, state-of-the-art HSC Winnipeg Women’s Hospital was the largest capital health project in the history of Manitoba – at 388,500 square feet, it is more than three times larger than the existing clinical space. The building houses a main-floor triage, labour and delivery, onsite Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and gynecology, antepartum, gyne-oncology units. Each inpatient room is private and features windows and natural light, a sleeping area for family support, a bathroom, and storage areas for personal belongings and required medical equipment.

Diagnostic Centre of Excellence and Heliport

The seven-storey, 91,000-square-foot centre is located on William Avenue and linked to the Children’s Hospital, the Ann Thomas Building and the new Women’s Hospital, housing a number of new pieces of diagnostic equipment including a new pediatric MRI, new CT scanner, a digital radiography suite incorporating existing equipment from the Ann Thomas Building, and a new operating room angiography suite. This building was the first in Manitoba to have a heliport and provides direct elevator access to the Ann Thomas Building emergency rooms and operating theatres.

Ambulatory Care Clinic at 700 Elgin Ave

Opened in fall 2022, the new Ambulatory Care Clinic brought together staff and services from multiple subspecialties into one, well-designed space on HSC’s campus. The building is now home to twelve internal medicine specialty clinics that were once located in seven different areas, providing more convenient experience for patients who can book multiple appointments at once, access several specialists in one place and reduce travel time.

Acute Stroke Centre – coming soon

Construction is underway of a new, dedicated 28-bed acute stroke unit that will be housed in the former Women’s Hospital at 735 Notre Dame Ave. It is anticipated that the acute stroke unit will open in 2023.

HSC by the numbers

- Located on 36 acres of land in central Winnipeg

- 780 funded beds

- Annually:

- 25,000 day-surgery procedures (18,000 adult and 2,500 pediatric)

- 7,000 gynecologic surgeries (Women’s Hospital)

- 120,000 visits to our Emergency Departments (70,000 Adult & 50,000 Children’s)

- 10,000+ patients arrive by ground ambulance

- 400+ patients arrive by air ambulance

- 25,000+ Adult admissions

- 6,250+ births (Women’s Hospital)

- 29,000 ambulatory care visits (Women’s Hospital)

Governance

Governance of HSC Winnipeg has transitioned several times, first in April 2000 when HSC Winnipeg was amalgamated with the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (WRHA), becoming an operating division of the Winnipeg Health Region. Then in 2019, as part of Manitoba’s broader Health System Transformation, HSC Winnipeg became a Shared Health facility, recognized as serving a vital role for health care delivery for all Manitobans.

Sources:

- Healing & Hope: A history of Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg (2009). Published by Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg, ISBN 978-1-55383-242-3; HSC Winnipeg Archives/Museum; and Annual Reports from the Winnipeg General Hospital, Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, Shared Health Soins Communs Manitoba

- Brian Sinclair inquest report (2013) https://www.manitobacourts.mb.ca/site/assets/files/1051/brian_sinclair_inquest_-_dec_14.pdf; The Provincial Implementation Team Report on the Recommendations of the Brian Sinclair Inquest Report (2015) https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/documents/bsi_report.pdf

Destination – Unknown?

Flood of 1950 Alumni Journal

By Aleda Greenway

Our 1950 flood had many facets. Probably for nurses, one of the most interesting was the method of handling the sick, and for the W.G.H, this meant several things.

It meant the necessity of suddenly opening the new maternity hospital in a matter of hours instead of the two weeks planned following the official opening. It took a great deal of concentrated effort to accomplish this. At this time everyone who could possibly do so worked at moving supplies and setting up wards complete with all linen, stationery, drugs and other equipment. The actual moving of the mothers and babies ran very smoothly. Some of our doctors were on hand to help too. It is interesting that the mother of the first baby born in the new pavilion had been previously evacuated from flooded Morris.

This stepped-up program of moving was done in order to make space for the patients coming from St. Boniface. These patients were moved by the army during the night necessitating a radio call for our staff to return to duty. The evacuees were fairly well settled by morning and then we had to help the St. Boniface nurses to fit into our situation. The task of connecting the patient, disease and doctor proved rather confusing and difficult. We were able to keep these patients happy during their stay with us. This was the beginning of our usefulness as a clearing station, receiving patients from nursing homes, other hospitals and flooded areas who were later evacuated to outside hospitals including some in other provinces.

When our turn came to evacuate patients from the General there had been time to make plans which worked well. The army had the total number who were to be moved, these divided into stretcher and ambulatory classes. The wards knew who were going and had each dressed, maybe in just a nightgown and house coat, with a brief history in an envelope bearing the name and former address pinned to the outside garment. In many cases the complete wordly goods were contained in a small paper bag clutched carefully by the patient. The hospital personnel, staff, students and orderlies were posted to move with precision, in bringing the patients down to the ambulances or the bus. One of the busiest people in loading the army ambulances was the driver of the street railway bus which was taking the ambulatory patients. He was very thoughtful of the patients.

Needless to say the attendant tension was high for many of us it was considerably increaded because of the weeping patients whose almost constant cry was, “where are they taking me?” Because we were under army orders we did not know the answer. All we knew was that the train was the next port of call. The fact that they would be taken care of was the only reassurance we could give. Their families and friends did not know that they were being evacuated. The Red Cross notified them later.

During that part of the flood time, we held ourselves in readiness for a call back on duty at any hour of the day or night, should mass evacuation prove necessary. Later our staff of graduates and students were divided into teams who took turns on call. The night on call was spent in one wing of the maternity pavilion, students of course were in their own rooms but available. However, as you probably all know this mass movement was not necessary so must of us were not called. When the danger was over we again served as a clearing station for some of the retuning patients.

Though the hospital itself was not seriously affected by flood waters we felt we had a very active part in the Flood of Manitoba.

Transplant Manitoba Milestones

50 years in the making

For more than 50 years, Transplant Manitoba – Gift of Life has been providing

organ donation services and kidney transplantation for Manitobans.

Follow our journey.

- 1967 – Dialysis unit opens at Winnipeg General Hospital (now HSC Winnipeg).

- 1968 – To prepare for the possibility of kidney transplant services, a committee of trustees, administration and medical staff spent a year determining if the Winnipeg General Hospital had the necessary facilities and staff to support it. A moral and ethics committee was also formed to establish recommendations and procedures to guide the process.

- 1969 – In October, the hospital’s Board of Trustees officially approved the life-transforming procedure.

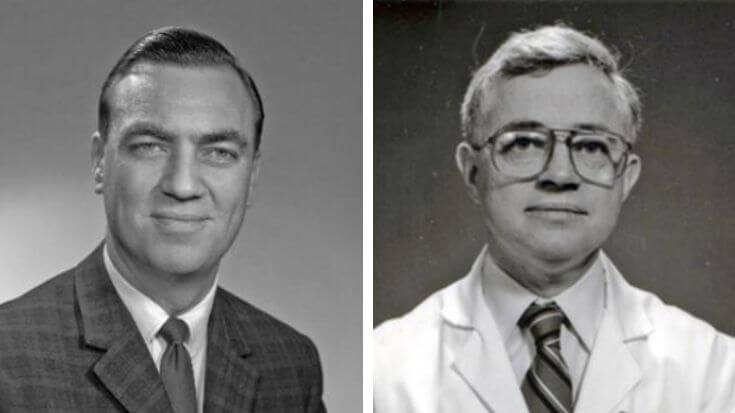

- 1969 – First kidney transplant performed in Manitoba in November. The team included Drs. Allan Downs, Ash Thompson, John Wade, John MacKenzie and W. Grahame. Learn more about this first surgery from one of the team members who participated in this historic event.

- 1971 – Living Kidney Donor Program begins.

- 1972 – Pediatric kidney transplant program begins.

- 1979 – Ten-year celebration. 178 kidney transplants to date.

- 1985 – Dr. John Jeffery held the position of Director, Manitoba Renal Transplant Program for nearly 20 years after retiring in 2005. Thanks to his vision, the program developed into what it is today, an internationally recognized centre for clinical and research expertise.

- 1994 – Lung transplantation begins in Manitoba.

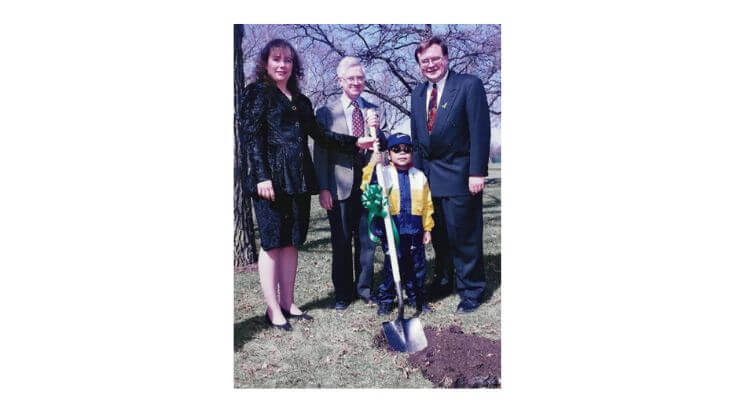

- 1997 – Introduction of the Tree of Life, a tribute to the generosity of organ donors. The first annual donor recognition event was held and leaves bearing the first name of every donor were placed on the Tree. Hundreds attended. The first Tree of Life event was held downtown at Eaton Place (now Cityplace) in 1997.

- 1998 – The Garden of Life begins to bloom in Assiniboine Park in honour of all organ and tissue donors. Breaking ground at Assiniboine Park for the Garden of Life during National Organ and Tissue Donation Awareness Week (NOTDAW) was in April 1997, with a donor mom and the provincial Health Minister.

- 1999 – A Canadian first – a double lung transplant using lobes donated by living donors.

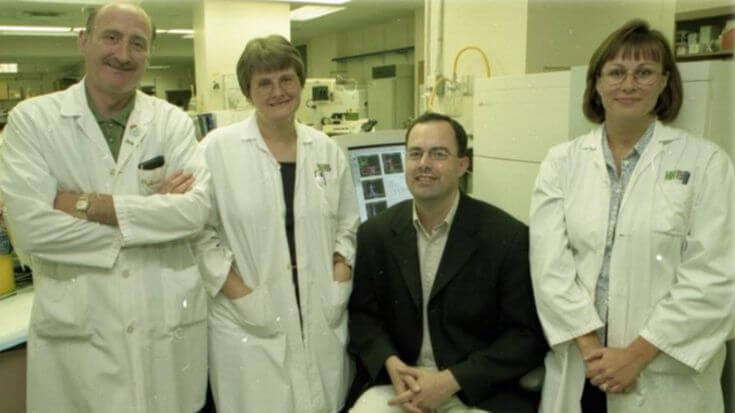

- 2000 – Using a Kidney Foundation of Canada – Manitoba branch grant to purchase a flow cytometer, medical director Dr. Peter Nickerson and the team began investigating whether flow cytometry cross-matching could prevent early graft loss by detecting lower levels of antibodies. Transplant Manitoba was the first centre in Canada to use flow cross matching as the standard of care.

- 2003 – Manitoba Transplant Program marks 1000 kidney transplants.

- 2006 – The Adult Kidney Transplant Program proposed the creation of an Organ Donor Organization (Gift of Life) and requested support from the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority for additional resources to improve access to transplant and promote an increase transplants performed. From the coordination of organ donation was handled by the Manitoba Transplant Program. In 2006, the program was renamed and restructured to Transplant Manitoba – Gift of Life.

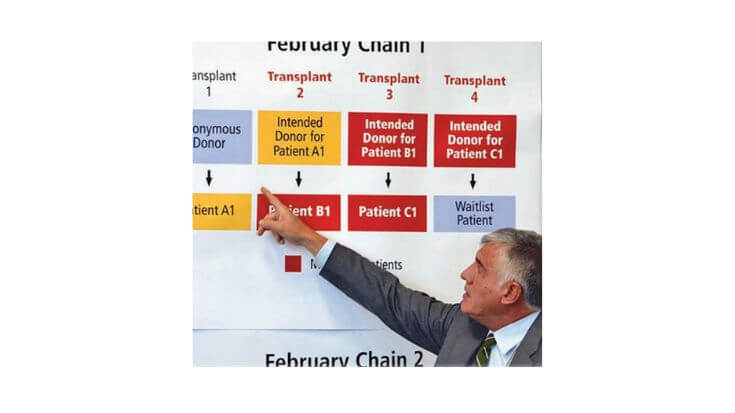

- 2009 – The national Living Donor Paired Exchange (now Kidney Paired Donation) Program begins.

- 2010 – Development of an organ donation and transplantation education resource, Life is a Gift, to support Manitoba’s Grade 11 Biology curriculum.

- 2012 – Two living kidney donor chains took place over three days in February at hospitals in five different provinces, including Manitoba for the first time.

- 2012 – Launch of www.signupforlife.ca Manitoba’s online organ and tissue donor registry.

- 2014 – To ensure families have compassionate end-of life care and the option to consider organ donation when the time is right, a mandatory referral policy, Routine Notification, was introduced in 2014. Since then, the percentage of all potential donors referred to the Gift of Life program has consistently improved.

- 2015 – Launch of the national Highly Sensitized Patient Program at HSC Winnipeg.

- 2015 – Donation after Cardiocirculatory Death or DCD becomes available in Manitoba offering more families the option to consider organ donation.

- 2015 – Surgical services within the Manitoba Lung Transplant Program are transferred to the Edmonton Lung Transplant Program.

- 2016 – Introduction of the Gift of Life flag with a donor family.

- 2017 – The Tree of Life is welcomed home to HSC Winnipeg by the team and a donor family.

- 2019 – Thanks to two anonymous gifts to the Health Sciences Centre Foundation, HSC Winnipeg will become home to a new, state-of-the-art Ambulatory Care Clinic for transplant patients at HSC Winnipeg.

- 2021 – The HSC Transplant Wellness Centre officially opened in April 2021.

No Smoking Policy

CentreScope May, 1973 Vol 1 No.6

***Disclaimer: this is a historical article and does not reflect HSC Winnipeg’s current policies***

A new policy restricting the use and sale of tobacco in the Health Sciences Centre has been determined and a target date tor the lull implementation of this policy will be announced in the near future.

Smoking will be absolutely prohibited in certain areas, restricted in others and actively discouraged in all areas of the centre.

Prohibited areas include all those which are now marked, plus several more. These will be shown by “No Smoking” and “Smoking Prohibited” signs, both at their points of entry and within, and include: emergency areas, intensive care areas, all tunnels, all corridors, all nursing stations, all stairways, all elevators, stall locker rooms and stall washrooms.

Large tank-type ashtrays with signs reading “No Smoking” and “Thank You tor not Smoking” will be placed throughout the centre. Signs at the nursing stations will ask visitors to retrain from smoking in patient rooms and visitors’ ward passes will carry messages to discourage smoking.

However, smoking will be permitted in the cafeterias, stall and visitors’ lounges and private offices.

The vending machines for cigarettes in use at present will remain.

The decision to form a more stringent policy regarding smoking began with a resolution passed by the Medical Staff of the former Win nipeg General Hospital and ap proved by the Board of Trustees. The Employee-Management Ad visory Committee of the hospital also supported this policy.

On May 4, 1973, the Board of Directors of the Health Sciences Centre approved the adoption of the policy for the entire centre. Large ashtrays with appropriate signs have already been placed in some locations with more to be added, to acquaint staff and visitors with the changes.

It is hoped the new policy will make both the staff of the centre and the general public more aware of the hazards to health caused by smoking.

More About No Smoking

CentreLine June 1973 Vol 1 No 7

July 1, 1973 has been selected as the date of implementation for the “No Smoking” policy.

During June additional ashtrays and signs will be located throughout the centre.

Signs are now being placed in the canteens at the General and Rehabilitation centres informing all patrons that as of July 1 tobacco products and matches will no longer be sold by the canteens. In addition, the White Cross Guild of the General Centre will discontinue the sale of matches and tobacco products from their travelling gift cart as of July 1.

All content is copyright HSC Winnipeg, [email protected]